Thus we could say that the 'I' is non-external; and hence that it is by definition in the realm of non-difference, or what we termed the "One". Now of course there cannot be two 'things' in non-difference, since that would imply duality and separateness - so the 'I' and the One must be not merely the same, but must be identical. Eckhart often uses the word 'soul' for what we mean by 'I'.

The soul is not like God; she is identical with him. (Eckhart) [14]

Soul and Godhead are one. (Eckhart) [15]

Know the One as the real 'I'. (Shankara) [16]

God and I are both the same. Then I am what I was, I neither wax nor wane, for I am the motionless cause that is moving all things. (Eckhart) [17]

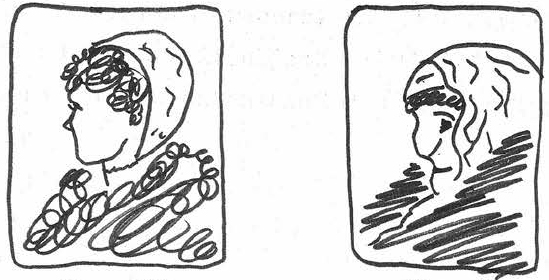

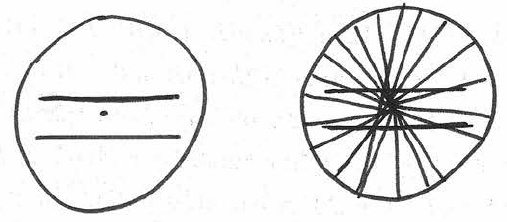

Now the One, by virtue of its possessing no separateness, must be everywhere and have no limits, as we saw our Knowers testify in the last Chapter. In fact, we can go further and say that if non-difference is everywhere and in all places, then the difference and diversity which we experience cannot exist. If the diverse did exist, then some part of the One (which is everywhere) would contain diversity and difference, which cannot be the case since we defined the One as being entirely non-differentiated. However the diverse obviously does exist - we have been examining its effects in Parts One the and Two, and took the Unpeace which it generates as a starting point of the whole book. We will deal with the paradox in the next chapter, but for now we notice that although the One is by definition everywhere, it is only as the 'I' that its nature of non-difference is evident. Thus while the One manifests in some way as the diverse, for practical purposes, ie for us to Know the One, we must look to the 'I', for that is identical with the completely non-differentiated One, the Godhead, as we have seen.

So we can see from all this that in order to Know rather than just to know, we have to look to the 'I' - that which is non-differentiated and non-diverse. The 'I', by virtue of being non-external is inside us - in fact is us, our heart and essence, and it is to this point 'within' us that we have to look.

Man's heart is the central point. (Shabistari) [20]

Turn to thy heart, and thy heart will find its God within itself. (Law) [21]

Let me know me, Lord, and I shall know Thee. (Augustine) [22]

When you attain to full realisation, you will only be realising the Buddha-Nature (ie the One) which has been with you all the time (Huang Po) [23]

Begin to search and dig in thine own field for this pearl of eternity that lies hidden in it. (Law) [24]

Here, within this body, in the pure mind, in the secret chamber of intelligence, in the infinite universe within the heart, the 'I' shines in its captivating splendour, like a noonday sun. By its light, the universe is revealed. (Shankara) [25]

Do thou all within. (Augustine) [26]

Pray within thyself. (Augustine ) [27]

The finding of the One or the Godhead 'within' is what we have termed 'Knowing'. But note that this Knowing is not discursive, nor depends on any difference, for the 'I' which looks inside for the One, is the One itself. So there is no duality. And for this reason, Knowing is not experiencing - it is union. For experience can only operate in the world of difference and duality, since any experience has at least two parts - the experiencer and the thing experienced. But when the experiencer (the 'I') and that which is experienced are the same thing, the One, then we are in a realm beyond experience - there is complete merging or union.